In this short book (116 pages, excluding references and index) Key and Tudor engage with some of the concepts and controversies surrounding this growing area of practice, asking, ‘how can we make sense of the field of ecotherapy?’ They bring together a theoretical survey with voices from the field.

The main text opens with a scoping review, seeking to make sense of a broad range of practice and theory: Indigenous psychology, Indigenous psychotherapy, environmental psychology, ecopsychology, ecopsychotherapy, terrapsychology, adventure therapy, ecotherapy, nature therapy, nature-based therapy, wild therapy, shamanic practice, outdoor yoga, despair and empowerment work, rites of passage work, forest bathing, and wild mindfulness all receive consideration.

In response to questions raised by this broad lexicon, the authors turn to exploring dialectic pairs (humans and nature, therapy and therapeutic, wilderness and wild, physical and metaphysical, culture and indigeneity, skin-bound self and ecological self) to think through semantic difficulties, cultural assumptions, and their implications for practitioners, clients, and the broader social and ecological fields in which practice is located. They remain alert to questions of power throughout – from the effects of regulation and standards in therapeutic practice, to the harmful repercussions of cultural (mis)appropriation, racism, (re)colonialism and (re)traumatisation.

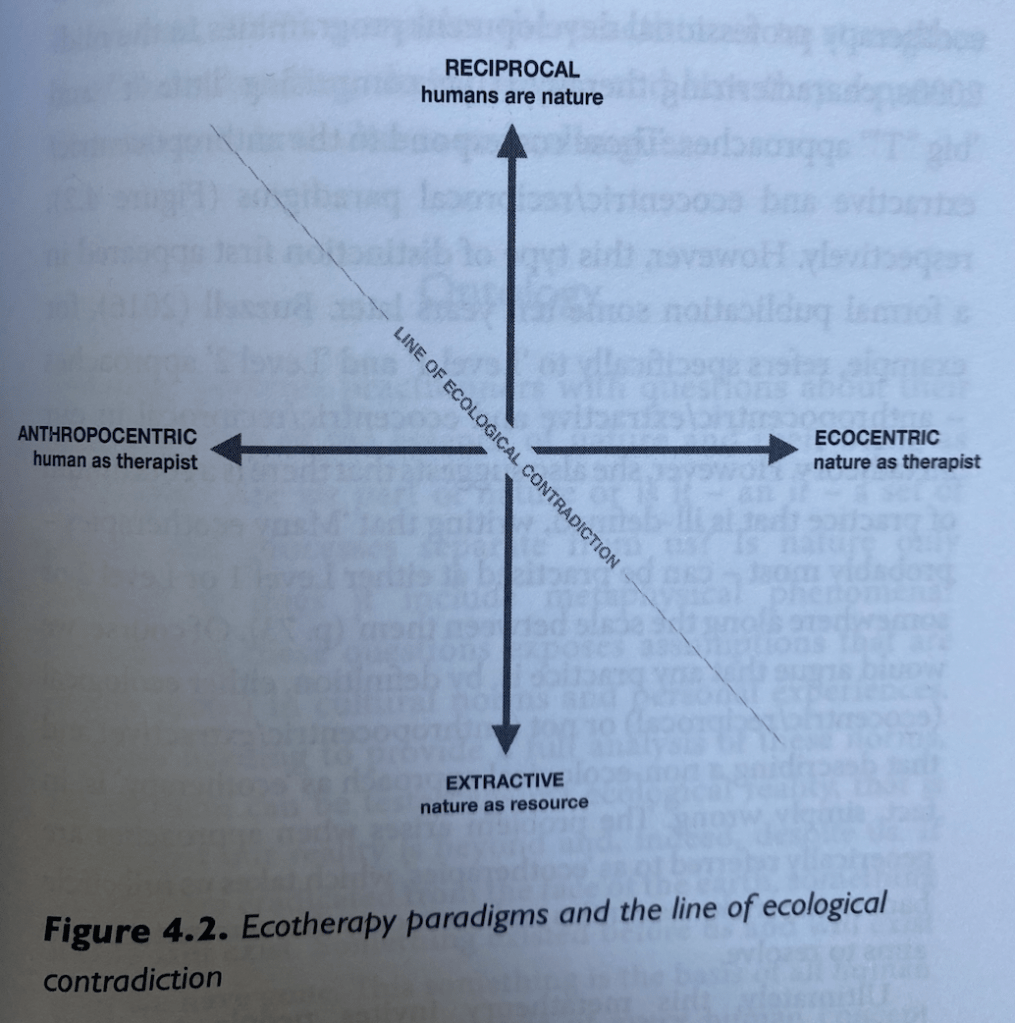

Recognising from their scoping review that current nomenclature within the field isn’t adequate, accurate or (they argue) congruent, Key and Tudor abandon their desire to organise practices by name ‘in order to allow a more useful taxonomy to emerge’, creating instead a metatheoretical model:

While reducing anything to something that can be plotted in two-dimensional space inevitably restricts as much as it reveals, I find this a simple and accessible way of thinking through my own growing practice along the axes the authors describe; its ontology (its essence), its axiology (its ethics and values) and its epistemology (its theories of knowledge). Would a truly ecological ontology require a two-person-plus psychology? What are the power dynamics inherent in how we describe our (human) relationship with nature? What theories of knowledge occupy the field?

While the authors outline the latter, and their associated research methodologies, I would have liked to have read a little more on ways of knowing within the therapeutic relationship as distinct/different from research methods (even if there is some overlap). That said, for me at least, this is a good opportunity to turn back towards, and reflect more deeply on, the core beliefs inherent in my own integrative therapeutic model. This is perhaps the authors’ aim for the book:

‘We suggest that thinking more philosophically about practice and striving for greater philosophical congruence – that is, of personal philosophy, the philosophy of a particular approach and practice . . . – enables the practitioner to strengthen their understanding, their practice and how they represent themselves to both clients and colleagues’ (p. 69).

I find this invitation to think about practice both valuable and welcome. Although not entirely new to the idea of integrating ecotherapy into my counselling practice, I’ve reached a point where it feels important and necessary to think more deeply and with more space for complexity.

In reading the book, in many ways I felt like I was on familiar ground and walking old paths: in developing their theoretical approach the authors draw on cultural theory (a substantive part of my own academic work before I retrained as a counsellor) and deep ecology (part of the soil, and soul, of Dartington, where I studied). I felt at home in this fertile mix, but it may be newer for others – especially those coming from more ‘medical model’ backgrounds. The important element, for me at least, was for the practitioner to be able to locate themselves and their work. As Key and Tudor note, ‘as all practice is founded on theory, and all theory is underpinned by philosophy, it is important for practitioners to know their theory and the ground on which they are standing – a point that seems particularly pertinent for ecotherapists’ (p. 114).

The final chapters of the book go some way towards re-invigorating and re-entangling that which cannot easily be contained or communicated in a theoretical schematic – locating theory back on the ground. The responses of colleagues (including indigenous people and practitioners who aren’t clinical psychologists or psychotherapists) provides space for hearing and honouring other voices and different ways of knowing, space for the emotion that comes with acknowledgement of wounding, and space for the ancestors. The authors’ offer their own recognition that presenting a model divided in half (a dualism) requires some troubling in order to give space to thinking about complexity.

I found this book to be a gentle, supportive challenge to practitioners to think their way into a relational, reciprocal and ethically-rooted practice.

Ecotherapy: A Field Guide by David Key and Keith Tudor.

Bicester: Phoenix/Karnac, 2023.